Volume 13 Issues 12 December, 2023

Dr. Ajay Kumar1

Editor, MINDS Newsletter

Military personnel from all nations routinely face challenging situations during their duty. Strong leadership and camaraderie are crucial for maintaining psychological resilience. While most manage these effectively, some inevitably experience distress, and a smaller proportion may develop mental health issues. Military success depends not only on superior firepower and numbers but also on the psychological resilience of service members.

- Department of Psychiatry, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, Raipur (Chhattisgarh).

INTRODUCTION

Military and paramilitary workers are often exposed to extreme stressors and life-threatening situations due to the nature of military service. Their psychological trauma leaves immediate reactions and even life-long impressions. Hence, first aid stabilises an injured person before professional medical help arrives. Just as physical first aid addresses immediate physical injuries, Mental Health First Aid (MHFA) provides crucial support to those experiencing mental health crises until they can receive professional treatment or the crisis subsides.

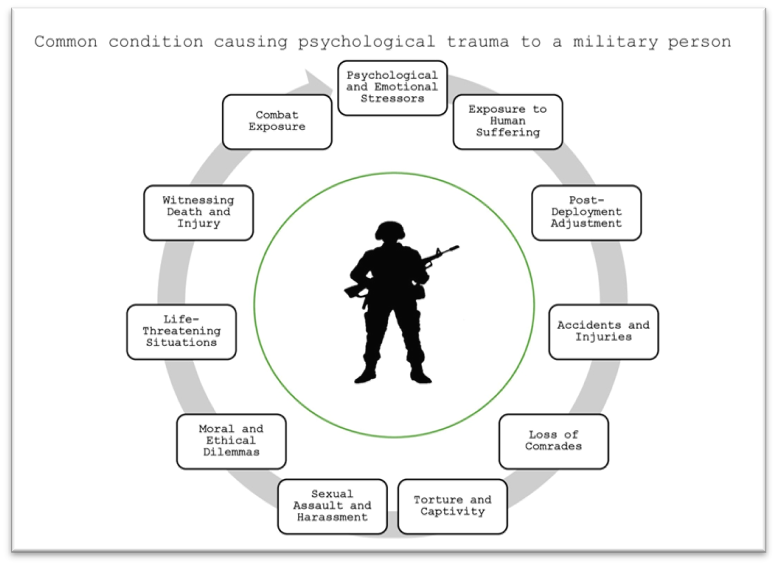

Common situation causing psychological trauma:

1. Combat Exposure

- Direct Combat: involves engaging in direct combat and witnessing the death or injury of fellow soldiers, enemies, or civilians.

- Firefights and Explosions: Being involved in firefights, bombings, or improvised explosive device (IED) attacks.

2. Witnessing Death and Injury

- Witnessing Casualties: Seeing the death or severe injury of comrades, civilians, or enemy combatants.

- Handling Bodies: Having to handle dead bodies or body parts can be particularly distressing.

3. Life-Threatening Situations

- Ambushes: Experiencing ambushes or surprise attacks.

- Survival Situations: Situations where survival is uncertain, such as being stranded or lost in hostile territory.

4. Moral and Ethical Dilemmas

- Moral Injury: Experiencing situations that challenge personal morals or ethics, such as having to kill in combat or witnessing or participating in actions that go against one’s ethical beliefs.

- Collateral Damage: Involvement in or witnessing actions that result in civilian casualties.

5. Sexual Assault and Harassment

- Military Sexual Trauma (MST): Experiencing sexual assault or harassment while in the military, which can occur regardless of gender.

6. Torture and Captivity

- POW Experiences: Being taken as a prisoner of war (POW) and subjected to torture, humiliation, or severe deprivation.

7. Separation from Family

- Prolonged Deployment: Long or repeated deployments away from family and loved ones, leading to feelings of isolation and homesickness.

- Family Strain: Stress from the impact of deployment on family relationships and responsibilities.

8. Loss of Comrades

- Death of Friends: Losing close friends or comrades in combat or due to accidents.

- Survivor’s Guilt: Feeling guilty for surviving when others did not, or feeling responsible for their deaths.

9. Accidents and Injuries

- Military Training Accidents: Experiencing or witnessing severe accidents during training exercises.

- Non-Combat Injuries: Suffering from severe non-combat injuries that can be physically and psychologically traumatic.

10. Post-Deployment Adjustment

- Reintegration Challenges: There are difficulties adjusting to civilian life after deployment, including issues with employment, relationships, and daily routines.

- Stigma and Lack of Support: Facing stigma or lack of support from civilian communities or institutions.

11. Exposure to Human Suffering

- Humanitarian Crises: They participate in humanitarian missions, where they witness extreme human suffering, such as famine, disease, and displacement.

12. Psychological and Emotional Stressors

- High-Stress Environments: Constant high-stress environments and the pressure to perform under dangerous conditions.

- Sleep Deprivation: Chronic sleep deprivation due to operational demands, which can exacerbate psychological stress.

The aims of mental health first aid are to:

- Preserve life where a person may be a danger to herself/himself or others.

- Provide help to prevent the mental health problem from becoming more serious.

- Promote the recovery of good mental health.

- Provide comfort to a person experiencing a mental health problem.

Military personnel from all nations routinely face challenging situations during their duty. Strong leadership and camaraderie are crucial for maintaining psychological resilience. While most manage these effectively, some inevitably experience distress, and a smaller proportion may develop mental health issues. Military success depends not only on superior firepower and numbers but also on the psychological resilience of service members. Despite the role of mental healthcare professionals, most psychological first aid occurs within units where supportive leadership significantly reduces mental health disorders (1–3).

GENERAL PRINCIPLES AND PRACTICE OF MHFA

MHFA is the help offered to a person developing a mental health problem, experiencing the worsening of an existing mental health problem, or in a mental health crisis.

The ALGEE Action Plan

The critical elements of MHFA are represented by the acronym ALGEE:

Approach the person, assess and assist with any crisis

The first step is to approach the person, look out for any crises, and assist the person in dealing with them. Key points include:

- Approaching the person about your concerns

- Finding a suitable time and space where both feel comfortable

- Initiating a conversation if the person does not

- Respecting the person’s privacy and confidentiality

Listen non-judgmentally

Listening is crucial. Non-judgmental listening makes the person feel understood and free to discuss their problems.

Give support and information.

Support includes emotional support, empathising with their feelings, offering hope of recovery, and providing practical help with overwhelming tasks.

Encourage the person to get appropriate professional help.

Inform the person about available help and support options. Professional help, such as medication, counselling, and psychological therapy, improves recovery outcomes.

Encourage other supports.

Encourage using self-help strategies and seeking support from peers, friends, and others. Peer support from those who have experienced mental health problems can be valuable (3).

SPECIFIC SITUATIONS

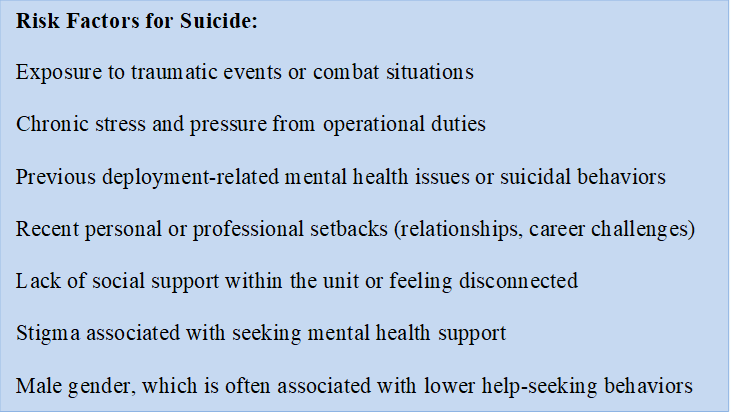

1. Suicide and Non-suicidal self-injury(3–5)

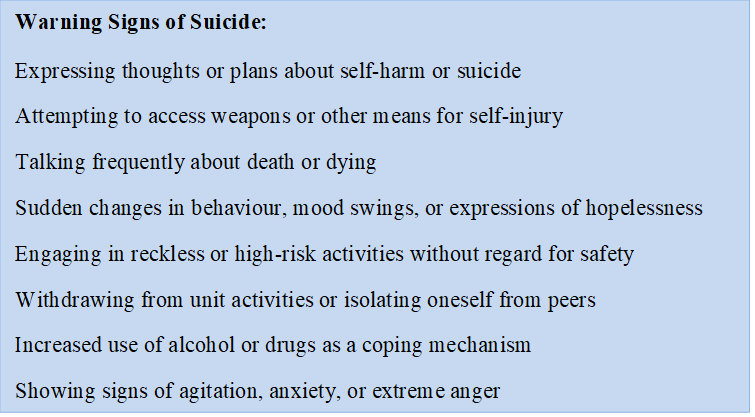

People may consider suicide to escape intense emotional suffering, convey their distress to others, or seek help they feel unable to request directly. Factors contributing to suicidal thoughts can include mental illness, physical health issues, recent traumatic events, or histories of abuse. Many individuals who contemplate suicide do not want to die but are seeking relief from unbearable emotional pain. Understanding and responding to suicide warning signs can be crucial in saving a life. Recognising these signs early and intervening appropriately can make a significant difference.

Approaching Someone in a Paramilitary Context About Suicidal Thoughts:

- Act promptly if you notice any warning signs or behavioural changes

- Approach the person calmly and respectfully in a private setting

- Express concern directly and ask about their well-being and state of mind

- Listen actively without judgment and validate their feelings

- Offer practical support and assure them that seeking help is a sign of strength

Validating Feelings

In paramilitary settings, where stoicism and resilience are often emphasised, validating feelings can be essential to foster trust and openness:

- Active Listening: Listen attentively and reflectively to what the person is saying. Use non-verbal cues such as nodding and maintaining eye contact to show understanding.

- Empathy and Understanding: Demonstrate empathy by acknowledging the person’s emotional pain and distress. Use phrases like “I understand this must be incredibly difficult for you” or “It sounds like you’re going through a lot right now.”

- Normalise Feelings: Assure the person that feeling overwhelmed or distressed is okay, especially in challenging circumstances. Validate their emotions by saying things like, “It’s understandable to feel this way given what you’ve been through.”

- Avoid Judgment and Criticism: Refrain from dismissing or minimizing their feelings, even if they seem disproportionate to you. Avoid statements that imply they should “snap out of it” or “be strong” without addressing the underlying issues.

- Encourage Expression: Create a safe space where the person feels comfortable expressing their thoughts and emotions. Validate their decision to seek help and reassure them that talking about their feelings is a positive step toward healing.

Managing a Suicidal Crisis in Paramilitary Settings:

- Take all signs of suicidal behaviour seriously and assess the risk level

- Develop a safety plan together, focusing on immediate actions to ensure safety

- Include emergency contacts such as unit leadership, unit health personnel, or support of unit members.

- Encourage the person to seek professional help and provide information on available resources.

- Maintain regular check-ins and follow-up to monitor their well-being

Developing a Safety Plan in Paramilitary Settings:

When dealing with a suicidal crisis in paramilitary settings, developing a safety plan is crucial to ensure the individual’s well-being. Here’s how to approach it effectively:

- Immediate Actions: Identify specific actions to help keep the person safe immediately. This might include removing access to any lethal means (e.g., weapons, medications), ensuring they are not left alone, and involving supportive peers or leaders.

- Identifying Triggers: Discuss potential triggers or situations that exacerbate suicidal thoughts. Understanding what triggers these feelings can help avoid or manage them effectively.

- Coping Strategies: Collaboratively identify coping strategies that the person finds helpful. This might involve physical activities (exercise, hobbies), relaxation techniques (deep breathing, mindfulness), or positive distractions.

- Social Support: List individuals within the unit or support networks whom the person can contact during a crisis. Emphasise the importance of connecting with trusted peers or leaders who understand the unique challenges of paramilitary life.

- Professional Help: Provide information about available mental health resources within the paramilitary structure or externally. Encourage the person to seek professional support and guide them on accessing these services promptly.

- Follow-up Plan: Establish a plan for regular follow-up and monitoring. Agree on specific check-in times and ensure they are consistently followed through to provide ongoing support and reassurance.

Approaching and Supporting Someone Engaging in Non-suicidal Self-injury(5).

If you suspect someone is self-injuring, approach them with care and empathy. To remain calm and non-judgmental, address your feelings about self-injury before initiating the conversation. Choose a private setting and express your concerns directly, making it clear you understand NSSI to some extent. For example, say, “Sometimes, when people are in a lot of emotional pain, they injure themselves on purpose. Is that how your injury happened?”

Avoid expressing strong emotions like anger or frustration; do not demand the person talk about their self-injury if they are not ready. Instead, focus on making their environment less distressing and their life more manageable. Encourage them to seek professional help and discuss various options with them. If they agree, assist them in finding appropriate mental health services.

2. Trauma and Stress

A potentially traumatic event is a powerful and distressing experience that threatens life or significantly endangers a person’s physical or psychological well-being. In context of paramilitary it could be anything ranging from an ambush to full on violent encounter in field. It could also include interpersonal violence (e.g., family violence, physical or sexual assault), accidents (e.g., traffic or workplace incidents), and witnessing severe incidents. Indirect exposure, like witnessing trauma or learning about traumatic events affecting others, can also induce trauma (3,6).

How Might Someone React to a Potentially Traumatic Event?

Reactions to traumatic events differ greatly among individuals. Common immediate responses include emotional upset, heightened anxiety, and disturbances in sleep or appetite. Other reactions might involve sadness, guilt, fear, or anger. Typically, these reactions subside within a month, but a minority may develop acute stress disorder or post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

Acute Stress Disorder and Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder

Both acute stress disorder and PTSD involve re-experiencing the trauma through recurrent dreams, flashbacks, or intrusive memories. There is also avoidance behavior, such as avoiding reminders of the event, and persistent symptoms of increased emotional distress, including hypervigilance, irritability, and insomnia. Acute stress disorder is diagnosed within the first month after the event, whereas PTSD is diagnosed when symptoms persist for longer.

What to do for a Potentially Traumatic Event

Maintain a calm demeanour and communicate as an equal. Show active listening and avoid discouraging expressions of feelings. Avoid minimising their experience or comparing it to others. Reassure them that their reactions are normal and understandable. Be prepared for expressions of survivor guilt and incomplete memories of the event.

Do not force discussions about the event or their feelings. Avoid interrupting, probing for details, or offering unsolicited advice. Do not imply fault or diminish their experience.

Responding to Challenges During the Conversation

Be patient and understanding of challenging behaviour. Allow breaks if the person becomes distressed. Help them stay grounded if they experience flashbacks. Find alternative support if needed.

How Can I Support the Person Over the Next Few Weeks or Months?

Acknowledge the fluctuating nature of their recovery. Offer information on resources and support services. Be mindful of triggers and anniversaries that may require extra support.

When Should the Person Seek Professional Help?

Encourage professional help if distress persists beyond four weeks, if they exhibit significant behavioral changes, if their relationships suffer, or if their symptoms interfere with daily activities.

3. Psychosis

Psychosis is a mental health condition that causes a person to lose touch with reality, significantly impacting their thoughts, emotions, and behaviors. In the paramilitary context, psychosis can be particularly disruptive, affecting operational readiness, team cohesion, and overall mission effectiveness. Mental illnesses such as schizophrenia and bipolar disorder are familiar sources of psychosis, which can also be triggered by extreme stress or substance use prevalent in high-stress paramilitary environments (3,7).

- Recognising Signs and Symptoms

Paramilitary personnel experiencing early signs of psychosis might display: - Emotional Changes: Unusual emotional responses such as depression, anxiety, irritability, and flat or inappropriate emotions.

- Cognitive Changes: Difficulty concentrating, suspiciousness, altered perception of reality, and unusual ideas or perceptual experiences.

- Behavioral Changes: Disturbances in sleep patterns, social withdrawal, reduced energy, and decreased ability to perform their roles effectively.

Actions to take

If a paramilitary colleague shows signs of developing psychosis, it is crucial to act promptly. Encourage Professional Help: Encourage the individual to seek help from mental health professionals. Offer to accompany them or assist in making appointments.

Stay Calm and Supportive: Approach the situation with empathy and patience. Listen to their concerns without judgment.

Respect and Dignity: Maintain the individual’s dignity and confidentiality throughout the process. Avoid making assumptions or labelling their experiences in a stigmatizing way.

Emergency Situations: If the person is in a severe psychotic state, characterised by intense delusions, hallucinations, or disorganised thinking, ensure they receive an immediate professional evaluation. Contact emergency medical services, providing clear and specific information about the person’s condition.

CONCLUSION

Paramilitary personnel are routinely exposed to challenging and traumatic situations, making them susceptible to mental health issues such as anxiety, depression, PTSD, and psychosis. The unique stressors of paramilitary service necessitate a robust understanding and implementation of MHFA principles within units. Leadership and peer support play a pivotal role in reducing the incidence and impact of mental health disorders by fostering a culture of psychological resilience and openness.

The ALGEE action plan—Approach, Listen, Give support, Encourage professional help, and Encourage other supports—provides a structured framework for delivering MHFA. Specific guidelines for handling situations like suicide, non-suicidal self-injury, trauma, and psychosis are essential in a paramilitary context, where prompt and appropriate responses can save lives and enhance unit cohesion.

In conclusion, integrating MHFA into paramilitary training and practice is vital for safeguarding the mental health of service members, ultimately contributing to mission success and overall resilience.

REFERENCES

- Keil K. Mental health first aid. Can Vet J. 2019 Dec;60(12):1289–90.

- Mohatt NV, Boeckmann R, Winkel N, Mohatt DF, Shore J. Military Mental Health First Aid: Development and Preliminary Efficacy of a Community Training for Improving Knowledge, Attitudes, and Helping Behaviors. Mil Med. 2017 Jan;182(1):e1576–83.

- Ivbijaro G. et. al. Psychological & mental health first aid for all. Wfmh.Global. 2016.Retrieved June 14, 2024, from https://wfmh.global/img/what-we-do/publications/2016-wmhd-report-english.pdf

- Ross AM, Kelly CM, Jorm AF. Re-development of mental health first aid guidelines for suicidal ideation and behaviour: a Delphi study. BMC Psychiatry. 2014 Sep 13;14(1):241.

- Chalmers KJ, Jorm AF, Kelly CM, Reavley NJ, Bond KS, Cottrill FA, et al. Offering mental health first aid to a person after a potentially traumatic event: a Delphi study to redevelop the 2008 guidelines. BMC Psychol. 2020 Oct 6;8(1):105.

- Cottrill FA, Bond KS, Blee FL, Kelly CM, Kitchener BA, Jorm AF, et al. Offering mental health first aid to a person experiencing psychosis: a Delphi study to redevelop the guidelines published in 2008. BMC Psychol. 2021 Feb 12;9(1):29.